I’ve always been a voracious reader, and that started as soon as I learned how to read. I used to love the Scholastic Book Fairs, and I almost always got mysteries. I think my grandmother loved mysteries, too, and that influenced me into that direction, as well as an early addiction to Jonny Quest1. My first exposures to series mysteries for kids was with Trixie Belden; The Red Trailer Mystery. When I was in elementary school, we had not only the school library but our teachers often had books in the classrooms we could borrow; my sister had borrowed the book from her class, and I loved it. I’d heard of the other series—the Hardy Boys and Nancy Drew—but neither the school library nor the public library another block away from the school carried them.

The first three Hardy Boys mysteries, original text versions, went into the public domain last year2--which is why there are so many editions of them available on various websites from different publishers. The Tower Treasure, The House on the Cliff, and The Secret of the Old Mill are also available on Project Gutenberg, along with many other books from the kids' series Grosset & Dunlap published over the years that have been long out of print--so if you're looking for ebook versions of certain Vicki Barr, Judy Bolton, Dana Girls, and Kay Tracey books, head over there and do a search and go to town (I certainly have). These books going into the public domain also sent me down a nostalgic path for a few hours, thinking about how I first discovered the Hardy Boys, and the pivotal role they played in my development, not just as a reader but as a writer. (I’d first heard of them with their animated Saturday morning cartoon series, in which they also were a "band"--kind of like the Archies, the Monkees, and Josie and the Pussycats--and I liked the show because, well, I liked mysteries.) The first time I ever held a Hardy Boys book in my hand was while visiting Alabama one summer and staying with a cousin of my mother's who was also her closest friend from childhood. Her son was an avid reader, like me, and also like me, liked mysteries.

The difference was his local library stocked the kids' series that my local library refused to. He had just been to the library and had a stack of mysteries on his nightstand. I picked up The Mystery of Cabin Island while he picked up a book from another series I'd yet to hear of, The Three Investigators. I was about a chapter into my Hardy Boys mystery when he asked if we could switch books. I said sure, handed him The Mystery of Cabin Island and he handed me The Mystery of the Moaning Cave, which was amazing. But after returning to school that fall, I found that our local Woolworth's carried the first three Nancy Drew mysteries and the first three Hardy Boys. Since the Hardy Boys were boys and for boys, my mom was so delighted that I wanted to read them that she bought me all three (me reading about girls and women was of great concern to my very young parents, and they discouraged me from that as much as they possibly could; which is the worst thing to do for someone as stubborn as me). I would rediscover the Three Investigators later, but collecting and reading the entire set of the Hardy Boys became an obsession for a young Gregalicious…one of my mental disorders is completion and I still will look for copies of volumes I don’t have in second-hand stores, yard and library sales.

I recently found a tweed, original text version of the Hardy Boys' thirteenth adventure, The Mark on the Door, at the library sale. I had never read the original text version, merely the revision from 1967. I am not a huge advocate for the Hardy Boys; yes, I collect them, and yes, I read them when I was a child and yes, they were a huge influence on me--but they were never my favorite of the juvenile series. They were, however, the books my parents approved of that also happened to be the most readily available everywhere. (I preferred several other series to them, especially The Three Investigators and Ken Holt.) I am a hobbyist collector because one of my many neuroses requires me to complete everything, and therefore, I have to complete the sets of all the series I read as a child. This becomes problematic with the earlier Nancy Drew and the Hardy Boys, because there are usually two editions for the titles in both series--the original texts (OT's) and the revised texts (RT's). These were also the two most popular series for kids, and so as not to kill the golden goose in the 1950s, the books began to be rewritten and updated, primarily to reflect technology changes as well as to remove dated and potentially offensive racist, sexist, and ethnic stereotyping. (Although they didn't think to edit out the fat-shaming of Chet Morton in The Hardy Boys series or of Bess Marvin in the Nancy Drews.) When I was a kid I preferred the revised texts--they were illustrated and the font was easier to read, and weren't quite as dated as the originals (the dialogue in the OT’s was much more formal and very unrealistic). Most purists, the aficionados and experts on collecting, prefer the OT's to the new--mostly because the RT’s also excised the personalities of Nancy and the Hardy brothers along with the dated, offensive parts. Since the world and societal mores had changed since the books were first published--the 1950's were dramatically different than the 20s and the 30s-- so obedience and obeying the rules and not being so headstrong and defiant of Authority was also written in, essentially castrating the Hardys and sterilizing Nancy, turning them into paragons instead of people. I've read all the revised texts of both series, but not all of the original texts--which I am trying to rectify now as an adult collector and (an obsessive) completer.

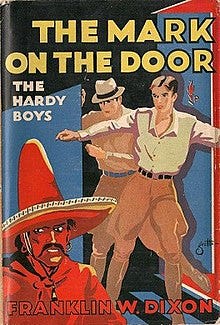

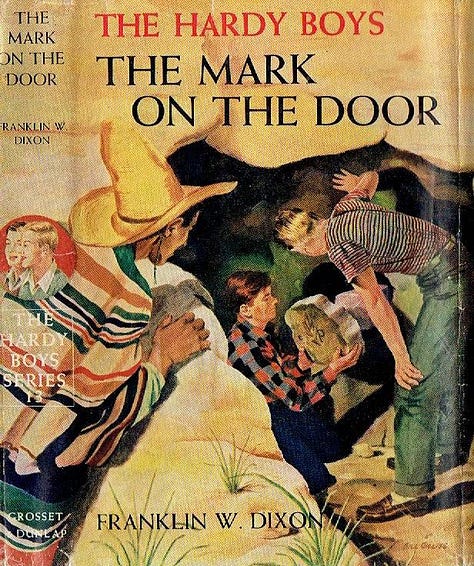

My copy from the library sale had lost its dust jacket, but here are the various covers over the years:

And as you can see, the cover art become slightly less racist over the years.

I belong to several fan groups on Facebook—for the Hardys, for Nancy Drew, for generic all kids’ mysteries—and one of the funniest things to me about said groups is how people there, long-time fans, are so adamant and demanding that anything other than how the Stratemeyer Syndicate envisioned them. They hated the modern adaptations into TV series (Nancy has sex! Ned is BLACK! Joe is way younger than Frank! And on and on and on), and many are purists for the original texts—with all the sexism, racism, and misinformation that came along with them. I wish I had a dollar for every time someone on one of those pages whined about “woke” or “politically correct” adaptations. The fragility of people’s childhoods is something that always bemuses me. Talk about an overreaction. No one is saying the stuff you liked about the characters and their stories is going away or can’t be read anymore or will be erased from your memory banks—one of the beauties of art is that it never goes away, even as it influences its observers or is reinvented or revised or updated for a more modern audience. Even as a child, I thought the two series were antiquated and quaint already…but they were aimed for ages 9-12, too. Is it any wonder that Nancy and the brothers were so damned chaste?

There is also a period—even for the aficionados—where the Hardy Boys books declined in quality and the stories became incredibly far-fetched (The Melted Coins, The Disappearing Floor, The Phantom Freighter) before returning to more traditional style kids’ mystery style with The Secret of Skull Mountain. When I was a kid reading the series for the first time, I’d made note of the “weird” stories, but as a completionist, kept going. Those books are the ones I’ve not read in the original texts…which were already prone to “this could never happen” type stuff in the first place.

So, I couldn’t resist paying a dollar for this tweed original text of one of the revisions I never cared for too much, and checking it out.

Based on the cover art, I was pretty certain the book’s original text was going to be racist, but there’s really not any way to prepare yourself for the full-on racism on display in this book. According to records, this was the last book in ghostwriter Leslie McFarlane’s original run with the series; but that' actual authorship is supposedly questionable, as the book’s style didn’t match his from the earlier titles. Among the hardcore Hardy Boys aficionados, McFarlane was the best writer in the history of the series; when i was a kid, of course, I thought Franklin W. Dixon was a real person. (Such a naïve and innocent child I was, really.)

The Mark on the Door…is a lot.

The book opens with the boys out on Barmet Bay in their motorboat, the Sleuth, when a sudden squall (which the bay is prone to) blow ups and they try to rush back to their boathouse before it gets too bad.3 But as they do, they realize they are on a crash course with another boat, and if not for Frank’s skillful steering, they only bump the other boat—side to side—but the other boat takes off and doesn’t stop…

The boys caught a glimpse of the man at the wheel. He was a swarthy fellow, black-haired, handsome in a way, but unpleasant looking. A moment later the big powerboat was racing away from them in a boiling flurry of foam.\

My alarms started beeping about now. “Swarthy”? Handsome, but looks unpleasant…that’s worded badly, because at first I thought “how can he be handsome but unpleasant looking?” before realizing he looked like he would be unpleasant. to deal with. As the story continues, Frank is determined to find “the swarthy man”. As they head back to the boathouse, Joe comments that the man was “foreign-looking.” Another alarm sounding…what does “foreign-looking” mean? Surely he didn’t look Russian or French to the Hardys, did he? Then they run into their friend Chet Morton, who doesn’t read the way I am used to; more of a pompous dandy: Chet was a fun-loving lad, and the butt of many jokes because of his desires for food. He was always hungry and he admitted it.

Well, not the worst fat-shaming I’ve read about Chet, I suppose. He convinces them to attend a trial at the courthouse with him, the Rio Oil Company fraudulent stock case. (Hilariously, part of the storm/boat crash adventure included the Hardys getting soaked through—but Chet doesn’t notice they are wet and they don’t seem to feel the need to change into dry clothes either on their way to the courthouse. Naturally, they see the “swarthy man” in the courtroom and try to catch him and “pay for the damage to our boat.” And then they run into Aunt Gertrude, who is being a bitch again just for the sake of being a crabby old bitch (it’s her default), but mentions the woman who owns a boarding house was bit by a “Mexican hairless,” given to Mrs. Smith by a Mexican boarder…and it occurs to the boys that maybe the swarthy man “could be a Mexican!” (Again, what precisely does a Mexican look like4?)

The book continues to be terribly racist. I do love that they flew from Bayport to Brownsville, Texas and it took them all night and most of the next day, including four plane changes, on their way south. There’s a “Mexican” stowaway on their plane, but once they land, no one seems to care to the boys and their father offer to take him home.

It really is terrible what racist Americans thought about Mexico, and its people, in 1934. Granted, most Americans knew very little about our Southern neighbor (they still don’t) and I remembered being very surprised on my first real trip to Mexico (not the college Tijuana trips) that it wasn’t what I thought it would be. Yes, there is crime in Mexico and horrific poverty, too—and drug cartels—but Mexico is no more dangerous than Miami or Houston or Dallas or Los Angeles. It’s also horrible to see just how recently these kinds of attitudes and mentalities not only existed but seen as normal and correct. But most Mexicans work very hard and are just trying to live their lives and do better for themselves and their children.

I finally gave up on the book when it turned out the stowaway had been kidnapped and sold into slavery up north (in the US, no commentary there about anything, of course) because a man got annoyed when their father wouldn’t let him date his daughter and so he kidnapped the son as vengeance.

Of course, everything in the book is connected—everything always is in the Hardy Boys’ world—so the criminals behind the Rio Oil scam, the kidnappers, and the man who hit their boat are all part of the same criminal enterprise they bring to justice in the end.

But The Mark on the Door is bad, even without the racism. Poorly written, poorly plotted, and everything hinges on coincidences and being in the right place at the wrong time—if their boat hadn’t been it, if they hadn’t run into Chet and gone to the courthouse…and on and on and on.

And it really makes me wonder about the original text purists, honestly.

It’s still my favorite kids’ cartoon of any kind.

Book four, The Missing Chums, joined them in the public domain this year; Hunting for Hidden Gold will go in 2025.

I’d love to know how many of their adventures began with this exact same trope—caught in a sudden storm on the bay. It’s definitely more than two.

Oh, I know precisely what they meant: Mexicans aren’t white—which is very racist and no different from saying someone “looks American” when they mean white.